TODAS

Nature: Installation

Description: Mahjong Set of 146 digital laser-engrave and UV print on ivory color hard plastic tiles, 2 extra tiles, a pair of dice, descriptive legend in a hunter green tactical box. (Edition of 5)

Dimensions: (37x27x15 cm / 14.6×10.6×6 inches)

Production Year: 2020

Exhibitions: ALT Philippines 2020, Manila, Philippines

Todas is an installation made up of a Mahjong Set (146 digital laser-engrave and UV print on ivory color hard plastic tiles, 2 extra tiles, a pair of dice, descriptive legend in a hunter green tactical box) set on top of a mahjong table with four (4) chairs. The set up invites the viewer to sit and play the game of mahjong whilst digesting the meanings of the artworks on each tile.

In Spanish, todas is a simple adjective that means “all.” Adopted into Filipino vernacular slang, it connotes something graver. It describes someone who is in big trouble, possibly at the verge of getting killed to pay back a debt. “Todas!” is also uttered when one wins in the game of Filipino mahjong.

TODAS invites its audience to leisurely participate in the game, whose tiles’ illustrations prompts critical dialogues amongst its players. It explores the socio-politically sensitive topic of the rapid influx of Chinese workers shoring up resentments amongst Filipinos over competition for jobs and property. This concern is aggravated by sentiments connected with the continuous Chinese military build-up on the reefs of the West Philippine Sea. According to Filipino diplomat Teodoro Locsin, POGO (Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators) is a Filipino invention designed to capture a greater share of the growing online gaming pie, indulging the Chinese with their own gambling vice, since it is banned in China. Do POGOs really bring financial gains for the average Filipino? At what costs? Do the gains to our economy outweigh the effects on our society? Is it true that the so-called ‘Chinese invasion’ is only a ‘lie’ to express anti- government sentiments? Is there a growing paranoia of Sino-Filipino connections despite the warmer relations between the current presidents? Haven’t the Filipinos traded and lived amongst the Chinese since time immemorial? Is this really an invasion of sorts? “‘Na-todas’ na ba tayo?” (Are we all done for?) Or are we in for the win, Todas.

TODAS is comprised of 144 custom-designs digitally printed on hard plastic tiles. There are four suits, each consisting of 36 tiles. Every mahjong tile references various perspectives on China’s globally expanding economic and cultural influence. TODAS is installed on a mahjong table ready to be played.

Word has spread far and wide, attracting collectors from places like Singapore and curators from institutions like London’s Tate Modern.

Replacing the bamboo sticks, this first suit consists of different calibre bullets. The Philippine eagle takes the place of the original number one stick tile of a bird sitting on a bamboo.

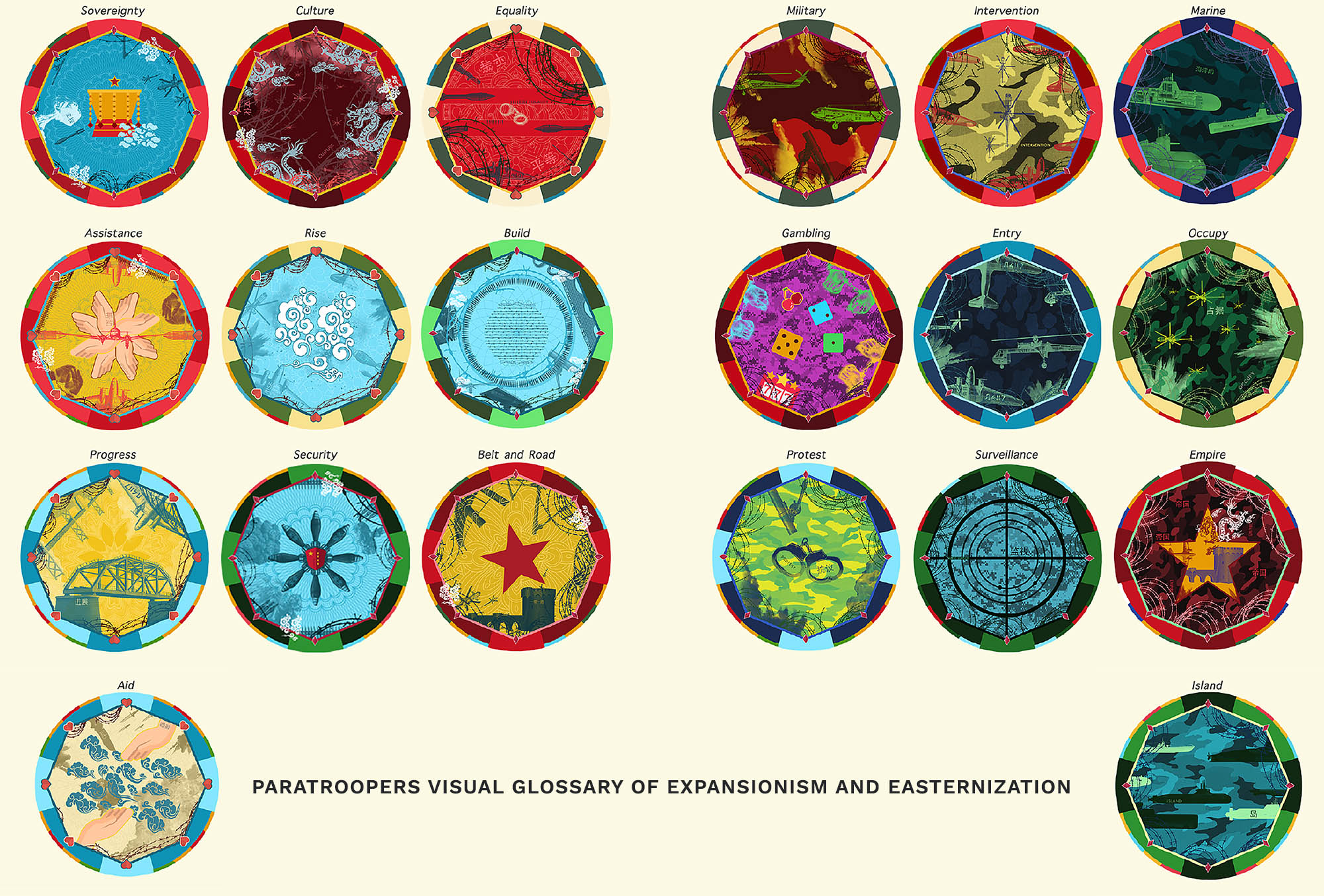

The second suit, replacing the dots/wheels, consists of the parachute designs from Josephine’s other work, Visual Glossary of Expansionism and Easternization. Replacing

the dots/wheels, which symbolize the traditional money/universal currency (tong bao 通寶), are individual gambling chips designed to illustrate ten positive and ten negative terms

associated with the global expansion of China, challenging diverse interpretations.

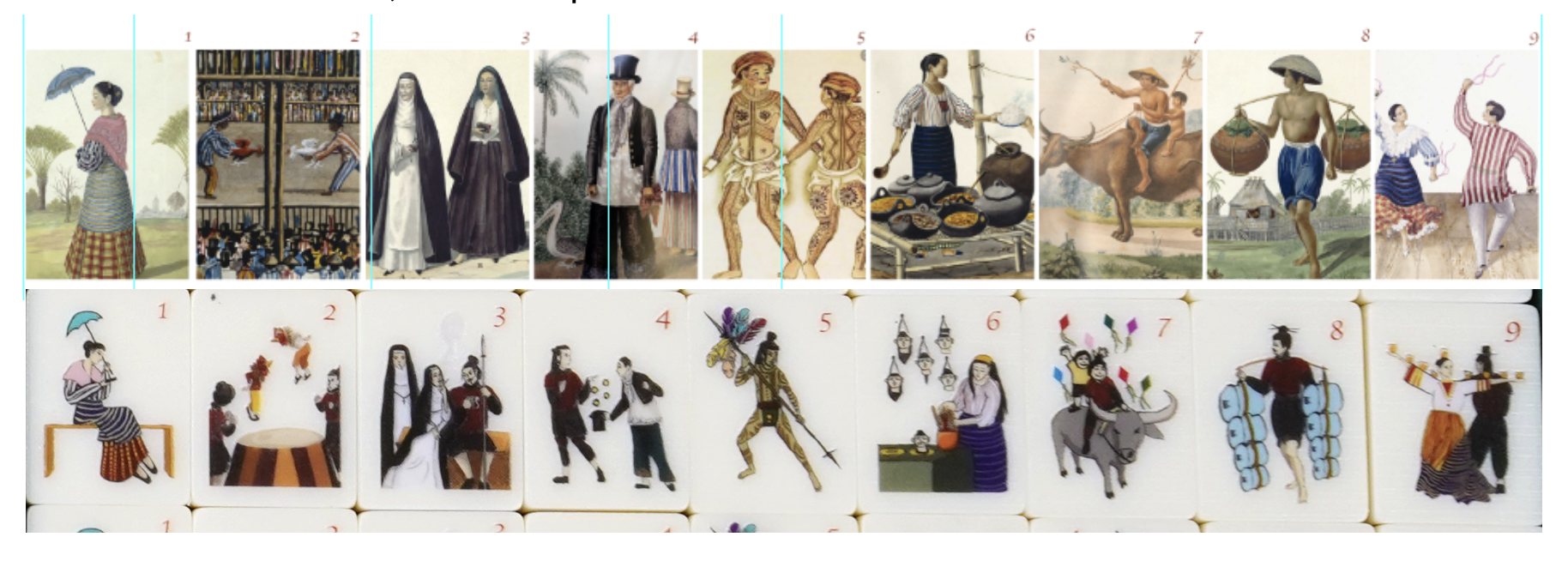

The third suit, replacing the characters/symbols, illustrates vignettes of interactions between stylized terra-cotta soldiers and Filipinos in the Spanish times, referred from the paintings of José Honorato Lozano. These illustrations include India de Manila, Interior de la Gallera, A.Madre Del Beaterio de Sta. Rosa B,Pupila de id, Un preso conducido por un cuadrillero y el gobernadorcillo, Carinderia, Labrador con su niño y una fonda, Aquador de Mariquina, El Cundiman. Tile number 5 alludes to a pintado warrior of the Visayas from the Boxer Codex, a manuscript written circa 1590.

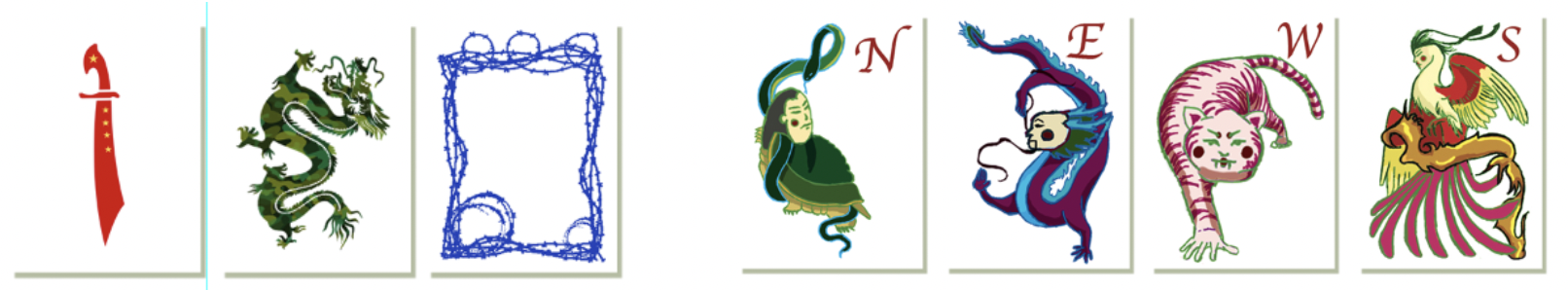

The fourth group consists of the flowers, seasons, and the honor suit of winds and arrows (dragons). An ancient Filipino sword substitutes the red dragon tile featuring a red 中

(zhōng, center), which connotes Confucian virtue of benevolence. The white dragon is a simple frame, symbolizing the higher or spiritual order of beings. Here, it is replaced by

barbed wire, implying isolation. The green dragon (fā 發, meaning wealth) also signifies the Confucian virtue of sincerity. The Chinese dragon is transformed to wear the military camouflage pattern.

The winds portray what is referred to as Chinese guardians, gods, or auspicious beasts of the four cardinal directions. These include the black tortoise of the North (commonly associated with longevity and wisdom), blue dragon of the East (Chinese dragons believed to be just, benevolent, and bringers of wealth and good fortune), the White Tiger of the West (was seen as a protector and defender), and the vermillion bird of the South (identical to the phoenix, a symbol of good luck). A reflection on the role of culture in the process of neo-geographic expansion is solicited with this suit. To what extent have Filipinos assimilated foreign cultural practices? Can we distinguish these amongst our everyday beliefs, traditions, and customs?

Replacing the season tiles are four areas of military operation: land, sea, air, virtual.

Flower tiles feature four out of seven reefs that China are currently occupying. “Burgos/ Gaven Reef, Calderon/Cuarteron Reef are high-tide elevations (above water at high tide). Panganiban/Mischief and Zamora/Subi Reefs are low-tide elevations (above water at low tide). Panganiban/Mischief Reef is within the Philippine EEZ (Exclusive Economic Zone) and forms part of Philippine continental shelf. Only the Philippines can erect structures or artificial islands on Panganiban/Mischief Reef.” (Carpio, Antonio T. (2017). The South China Sea Dispute: Philippine Sovereign Rights and Jurisdiction in the West Philippine Sea. Manila: Antonio T. Carpio, p.146.)

Only the special edition has two jokers: 2020 COVID 19 virus which originated from Wuhan province, China and the modern Terracotta soldier currency-armour, carrying a casino roulette as shield, phone on selfie stick.

Key Points of the South China Sea Arbitral Tribunal: THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES VS. THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA.

On 12 July 2016, The Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague rendered its award regarding the South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines versus The People’s Republic of China). This arbitration concerned the role of historic rights and the source of maritime entitlements in the South China Sea, the status of certain maritime features and the maritime entitlements they are capable of generating, and the lawfulness of certain actions by China that were alleged by the Philippines to violate the Convention.

- “The Tribunal Was Set Up To Consider The Role Of Historic Rights And Maritime Entitlements In The South China Sea, The Status Of Maritime Features, And The Lawfulness Of Actions By China That Were Alleged By The Philippines To Violate The Un Convention On The Law Of The Sea. There Were No Rulings On Sovereignty Over Land Territory Or Delimiting Any National Boundaries.

- China Refused To Accept Or Participate In The Arbitration, Which Was Initiated Unilaterally By The Philippines. This Was, In Itself, No Bar To The Case Proceeding Once It Was Decided The Tribunal Had Jurisdiction And The Claim Was “Well Founded In Fact And Law.

- There Is No Legal Basis For China To Claim Historic Rights To Resources Within The Sea Areas Falling Within The “Nine-Dash Line”, The Tribunal Said. (This Line Marks The Territory Claimed By China, Which Stretches Hundreds Of Miles South And East From Its Most Southerly Province Of Hainan). Although Chinese Navigators And Fishermen, As Well As Those From Other Countries, Have Historically Made Use Of The Islands In The South China Sea, There Is No Evidence China Has Historically Exercised Exclusive Control Over The Waters Or Their Resources.

- The Tribunal Considered Entitlements To Maritime Areas Based On The Features – Such As Reefs, Rocks Or Islands – That They Surround. Reefs (Which Have To Be Above Water At High Tide To Generate A Territorial Sea) Have Been Heavily Modified By China’s Land Reclamation And Construction Work, And The Un Convention Says Features Are To Be Assessed Based On Their “Natural Condition.” Therefore The Tribunal Relied On “Historical Materials” In Evaluating These Features, Rather Than How They Look Now.

- A Further Conclusion Was That Since None Of The Features Claimed By China Is Capable Of Generating An “Exclusive Economic Zone” From Maritime Entitlement, “Certain Sea Areas” Are Within The Exclusive Economic Zone Of The Philippines Because “Those Areas Are Not Overlapped By Any Possible Entitlement Of China”

- Having Decided That Some Areas Of The South China Sea Were Within The Exclusive Economic Zone Of The Philippines, The Tribunal Found That China Had Violated The Philippines’ Sovereign Rights There By Interfering With Fishing And Oil Exploration, Constructing Artificial Islands And Failing To Prevent Chinese Fishermen From Fishing There.

- China Has “Caused Severe Harm” To Coral Reefs And Violated Its Obligation To Preserve And Protect Fragile Ecosystems. The Chinese Authorities Are Aware That Chinese Fishermen Have Harvested Endangered Sea Turtles, Coral And Giant Clams “On A Substantial Scale” And Have Not Fulfilled Their Obligations To Stop This Aggravation Of Dispute.

- China’s Land Reclamation And Construction Of Artificial Islands Is “Incompatible With The Obligations On A State During Dispute Resolution Proceedings”, In Light Of Its Inflicting “Irreparable Harm To The Marine Environment”, Building A Large Artificial Island In The Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone And Destroying Evidence Of The Natural Condition Of Features That Were Key To The Dispute.How China has responded: China called the ruling “ill-founded” and said it would not be bound by it.

South China Sea tribunal: Key points. (2016, July 12). Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-36772813

PCA Press Release: The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China). (n.d.). Retrieved December 14, 2019, from https://pca-cpa.org/en/news/pca-press-release-the-south-china-sea-arbitration-the-republic-of-the-philippines-v-the- peoples-republic-of-china/