High Wire, High Seas

Art is necessary in order that man should be able to recognize and change the world. But art is also necessary by virtue of the magic inherent in it.

~ Ernst Fischer ~

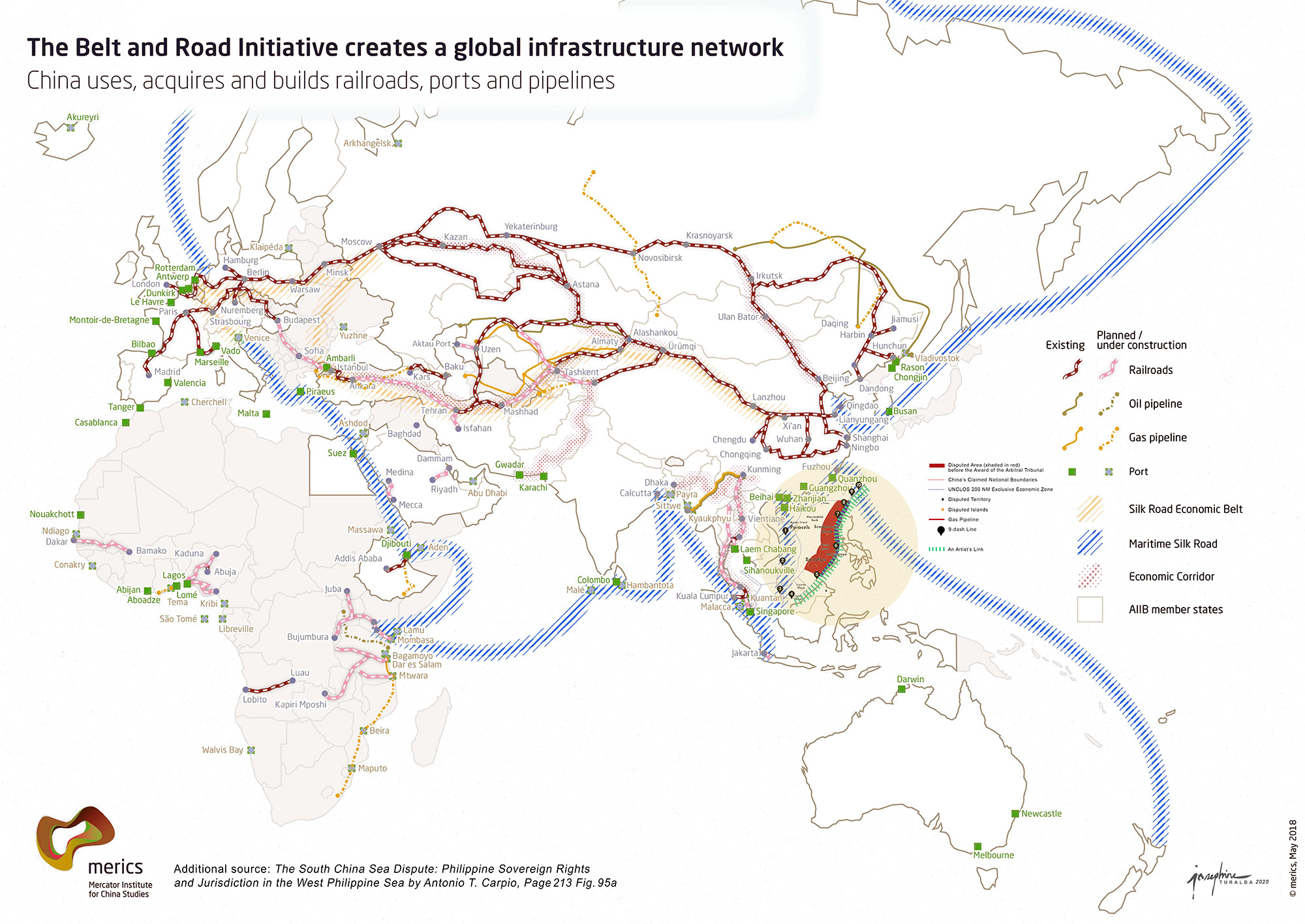

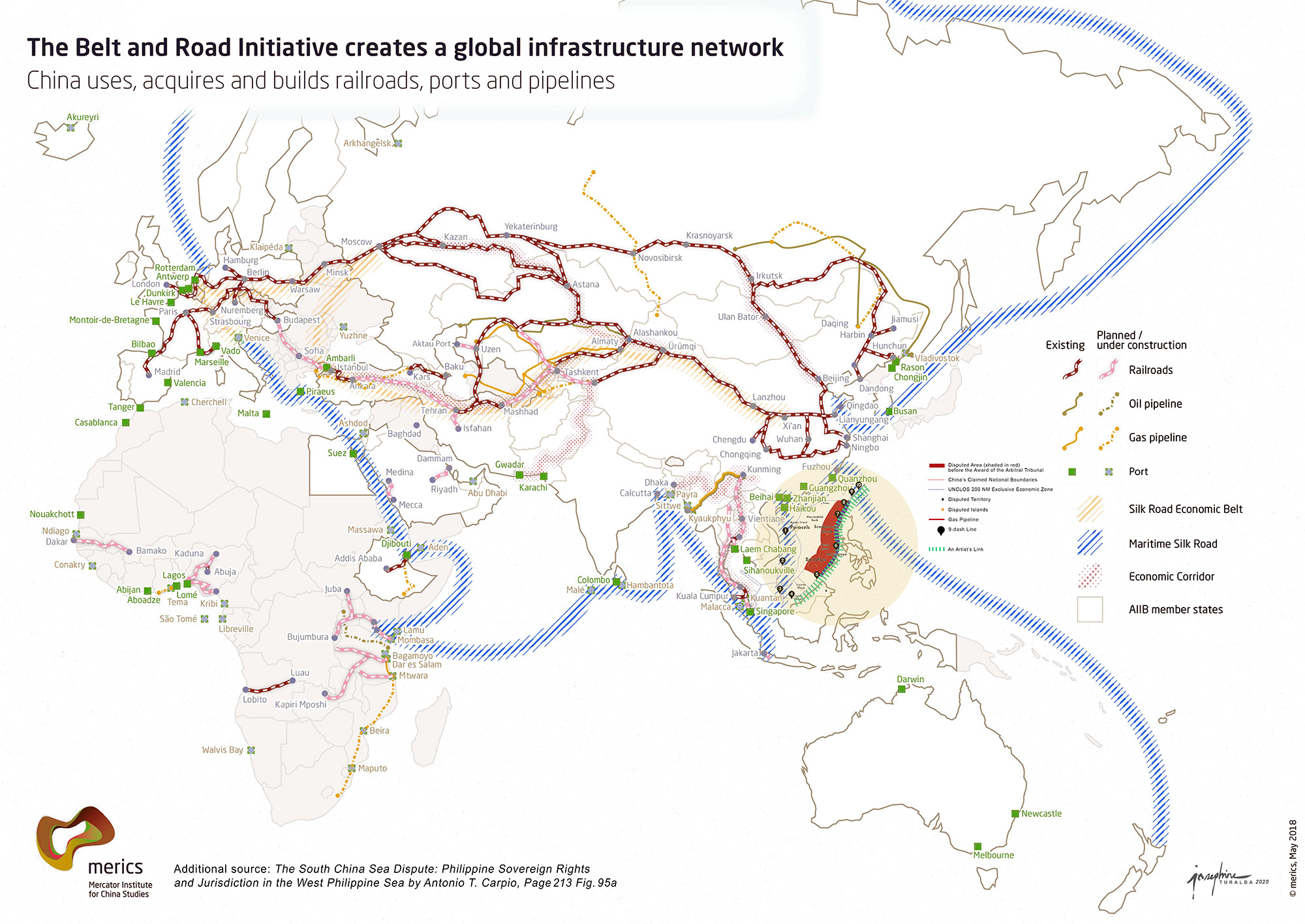

Multidisciplinary artist, Josephine Turalba’s second solo exhibition, High Wire, High Seas, at Galleria Duemila is timely, in light of China’s two strategic maneuvers in which the Philippines is, officially, an unacknowledged crucial player in the Asian region. Her multi-layered and often whimsical 36 pieces strategically arranged throughout the gallery can be seen as fragments of a larger geopolitical narrative installation attempting to connect the complex dots between China’s occupation of the Philippines-owned Spratly Islands and the global Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

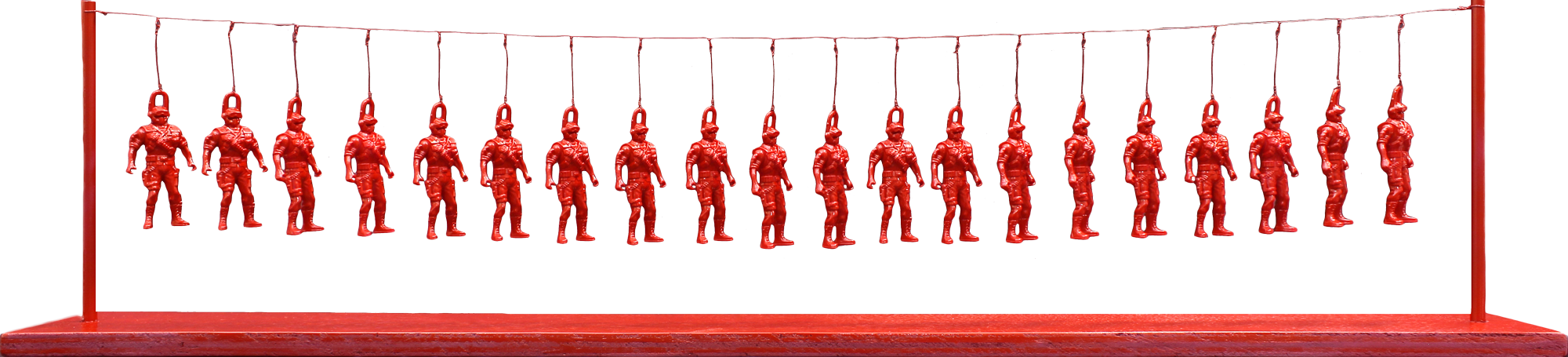

Josephine’s new body of work grapples with the pros and cons of China’s master plan for infrastructural investments in building railroads, bridges, ports, pipelines, IT and communications sectors, industrial parks, Special Economic Zones, tourism, and new cities. When she embarked on this project, the question she posed to herself is the same one she asks her audience – “Does this fear of invasion, stemming from the rapid influx of Chinese nationals, have a factual basis or is it all paranoia?” The fantasy world that she creates is grounded in a spectrum of facts and imagination in which her viewers become investigators of the fraught relationship between China, the Philippines, and the 65 countries that BRI programs are currently underway in. The perspectives of the political leaders, businessmen and citizens affected by the BRI change depending on whether or not these ventures are seen as mutually beneficial or as Trojan horses. Similar to the red army line of paratrooper toys in her Tightrope sculpture, Josephine’s own point of view ambiguously balances on a precarious high wire.

Her inspiration for this ambitious undertaking stems from a 2019 project which she produced for an exhibition in the Demilitarized Zone on the border of North and South Korea (DMZ) called DMZland (dmmm-zee-land). While researching in the DMZ, she became fascinated with the carnivalesque irony she witnessed there as South Korean tourists snapped selfies in a “Disneyfied” amusement park atmosphere, frolicking on and around the imaginary borderline between historic enemies who could go to war at any minute.

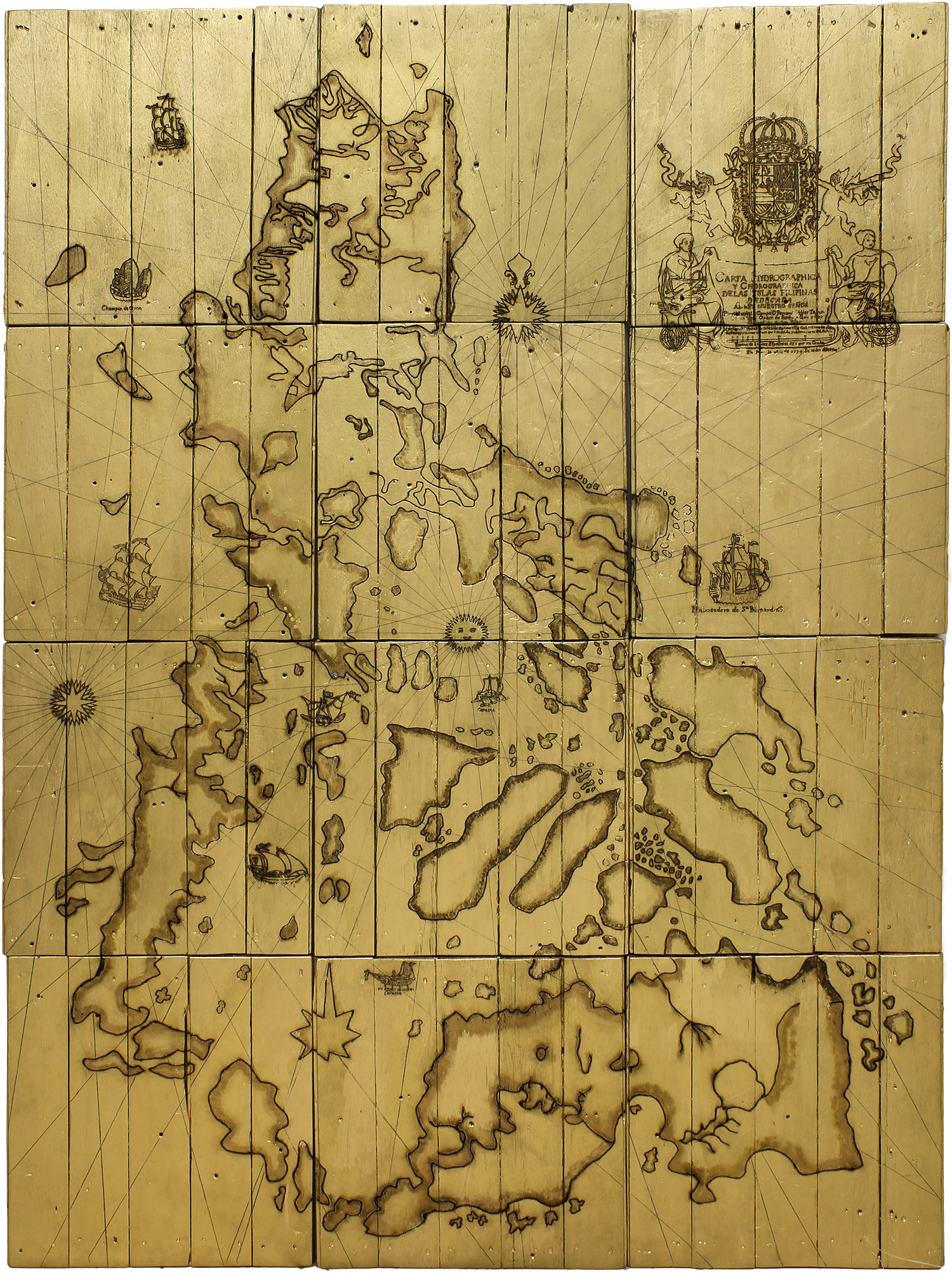

Key elements of Josephine’s DMZland—a life-size parachute made of actual parachute material, comprised of a collage of doll cut-outs referencing Disneyland’s It’s a Small World water-boat ride, icons of war and China’s penchant for gambling; framed panels made of left over parachute designs and a horde of red toy solider paratroopers—were reimagined and integrated into the High Wire, High Seas exhibition. The survival parachute transformed into a tent enclosing a pseudo military encampment with war paraphernalia scattered around the tent floor, nautical maps of the Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoals. In one corner, is a television blaring a montage of news footage from news agencies such as ABS-CBN, GMA 7, 60mins, Aljazeera, and Channel News Asia intercut with political analysts talking about the BRI at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and the Carnegie Council for International Affairs, and superimposed 3D animated humanoids, terracotta soldiers, gambling and military icons.

The video piece, Undercurrent, contains the intricate whole of the exhibition’s intentions, skillfully unifying the symbols repeated in many of the exhibition artworks and the social issues that they represent regarding the Spratlys and the new world order slowly, yet steadily being implemented by the all-encompassing Belt and Road Initiatives.

One hundred forty-five shiny red-painted army paratroopers swoop down from the gallery’s ceilings landing on the floor. Their colorful parachutes, made from a single discarded parachute, are imprinted with 10 positive and 10 negative designs. These photoshopped collages obtained from internet stock photos and illustrations of military planes, helicopters, submarines, barbed wire, playing cards, poker chips, dice, the Chinese dragon, camouflage, and other Chinese symbols are emblematic of China’s suspect “expansionism and Easternization” in the Philippines and the surrounding region. Single words like “culture”, “intervention”, “build”, and “occupy” are inscribed on some of the parachutes, punctuating what Josephine has identified as the various perspectives on China’s encroaching domination, not just in the Philippines, but around the world.

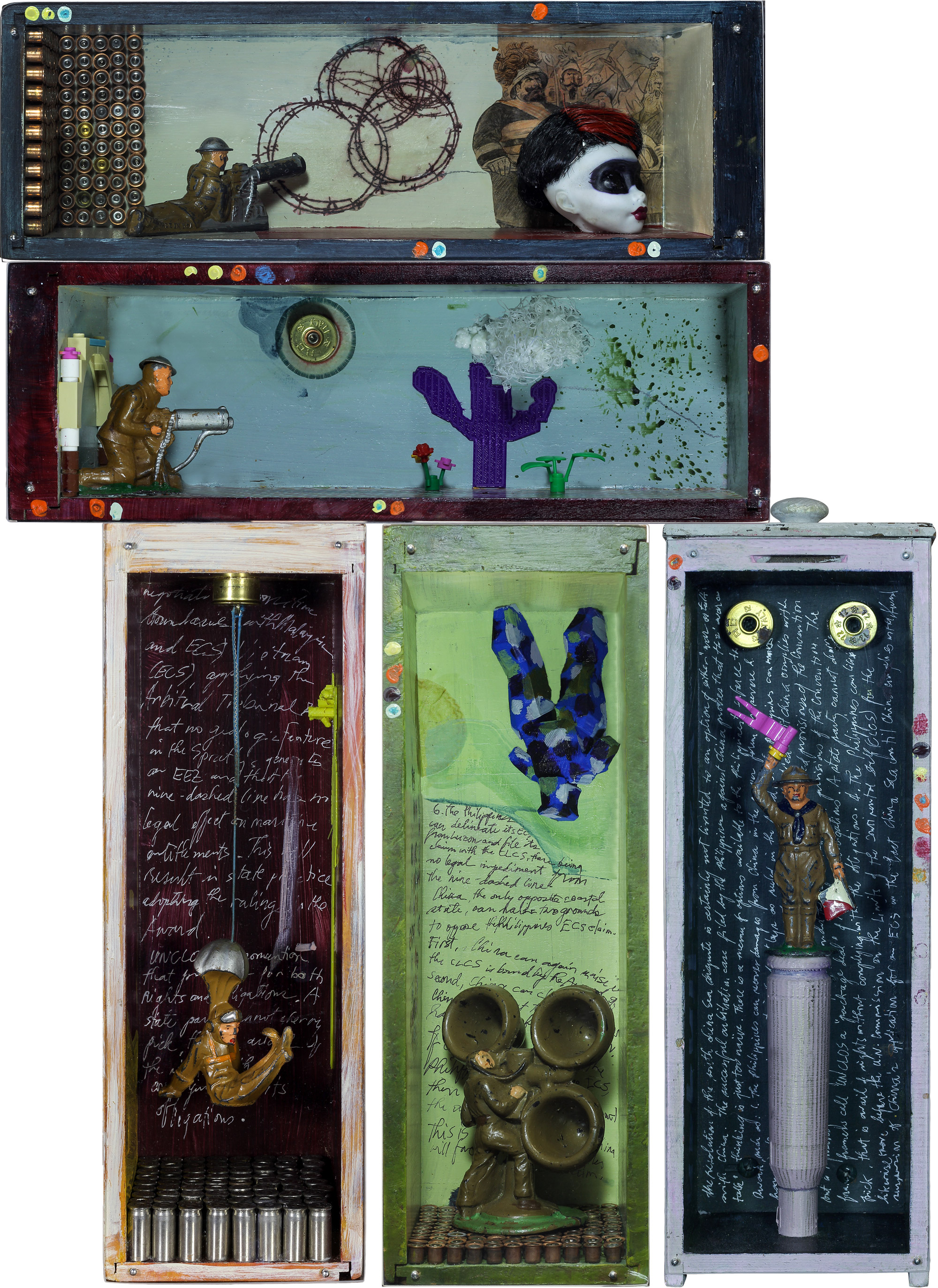

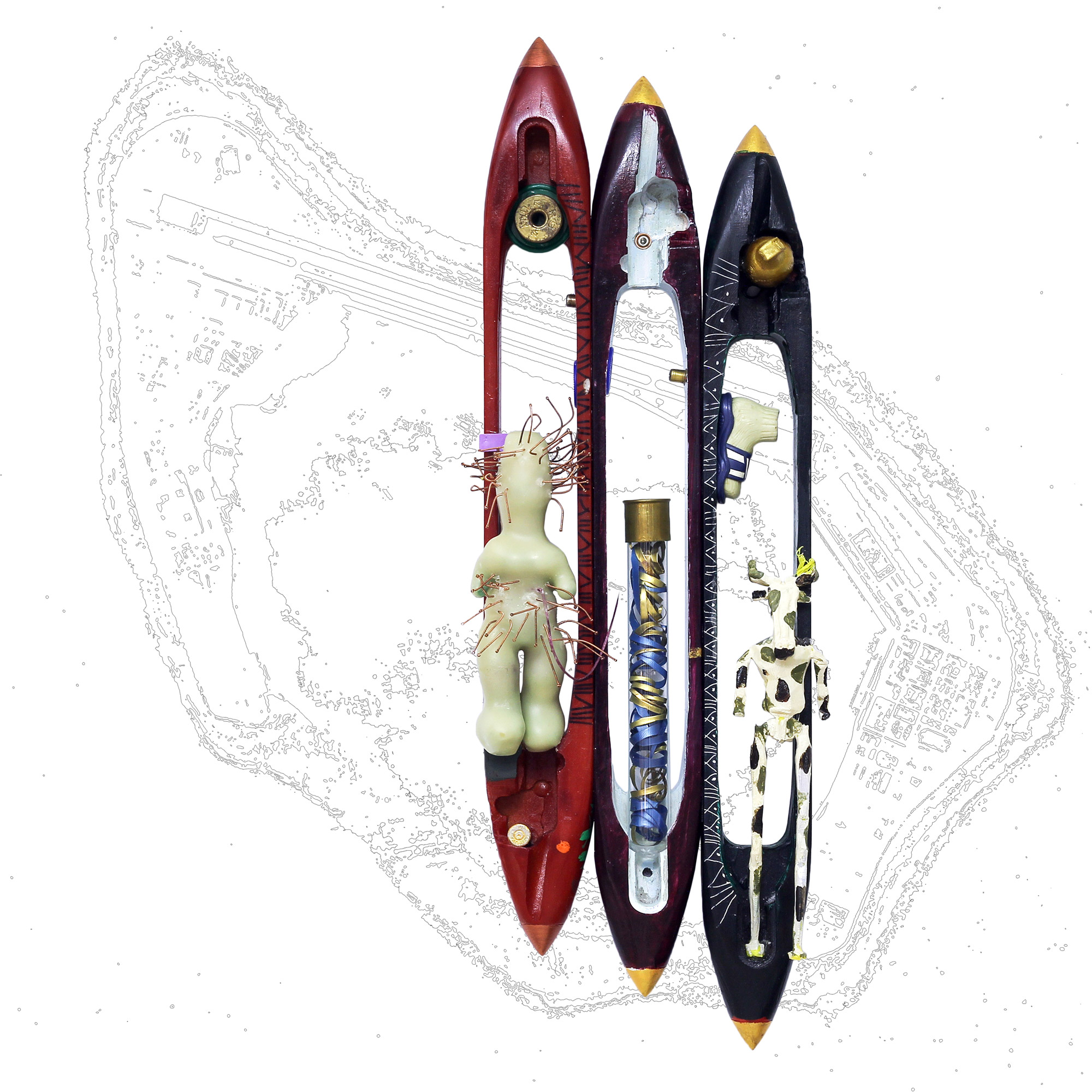

Her cunning titles, an extension of her circuitous way of thinking are calculated devices designed for the viewers to navigate through the exhibition’s politically sensitive subject matter. Nine multicolored found-object sculptures constructed out of wood and resin weaving shuttles consisting of upcycled children’s toys—Lego pieces, plastic doll and action hero body parts—are artfully juxtaposed with domino pieces, empty bullet cases and 3D printed humanoids and paratroopers (also seen in the Undercurrent video). They are cleverly assembled like fishing boats floating on top of impressionistic black and white aerial maps of the Chinese occupied and Philippines-owned territories in the South China Sea. The names of these reefs, shoals and islands accompanied by their corresponding geographic coordinates serve as their titles. The textural interplay of these objects and their meanings offset Josephine’s grave concern about China’s takeover of valuable seaways for trade and strategic military locations.

At the dawn of the second decade in the 21st century, the dictum “All roads lead to China” reverberates with varying truths depending on one’s perspectives on what can be gained, lost and found, and traded on the ancient Silk Road that connected the world together well before nations had names, visible and invisible boundaries established and disputed over and over again as wars were fought, and empires rose and fell. These well-traveled land and sea routes that brought a reciprocal kind of economic development and wealth around the world has resurfaced as China’s grand vision to sustain itself as a superpower.

High Wire, High Seas is on the cutting edge of critical artistic inquiry into social and political issues that we are living through today. Josephine Turalba seems to ask – “Is the BRI progress moving towards peace and economic growth world-wide or another form of imperialist economic dependence and colonial occupation through non-military aggressions?” The works in this exhibition, some of which are highlighted in this essay, are playful tongue-in-cheek red flags. (pun intended). However, upon closer examination, the artist appears to be calling for a more serious investigation into China’s policies and endeavors, and their effects on the Philippines, the region and globally. The understated tension in the works is perhaps a reflection of the artist’s apprehension to use the creative practice to support a singular point of view as a means to change the world. Instead, she is using the creative process to work through ways by which to inform her viewers of the dangers of China advancing a political agenda that may not be sufficiently challenged if the Trojan horse in the Philippines, remains unveiled. The mediums are the messages that are inevitably interpretable.

~ Angel Velasco Shaw, Reflections on Trojan Horses and Icons of War, 2020